Silence.

The absence of sound: the concept; the mindset; the state of existence. So rare. As a birder mainly working an inner London patch, it is not something I am used to. But sometimes (most definitely not always) it can be found on my other ‘patch’ in the French foothills of the Pyrenees.

South towards the Pyrenees

Arriving at the remote house, the silence hit me like a lump hammer. Miles from the nearest road, isolated from any flight paths, the patch is always wild. But the wild was silent too. No bird song, no bird calls (imagine the change from London: no gulls, no crows), no calling insects of the mediterranean. But also, no wind. Just cold air and bright sun. A frozen scene.

Birding the French patch is always a challenge. The birds are more secretive, far less visible, and sometimes silent. At first a sliver of panic set in: “are there any birds here at all?” – the foolish thought passed across my mind like an unwanted shadow.

Of course there were birds here, although the demographics had shifted quite significantly. The first bird I heard on the patch was a Blackbird; a low darting black shape and that ubiquitous furious squawking – its alarm call. But after an hour or so of walking around the maquis, I became aware of more and different thrushes. The chack-chacking of Fieldfare and occasional ripples of flocked flight from tree to tree that told me these winter migrants were here in large numbers. And then, the Song Thrushes. A bird I rarely see or hear on the patch – rather than the resident songbird that we know and love in the UK, and across much of Europe – these hilly foothills appear to be migrant territory only. Occasionally, the alarm calls took on a different pitch and the darting culprit was browner and more spotted than a female Blackbird. Over time, the thrush jigsaw was pieced together: Tens or even over a hundred Fieldfare and Song Thrushes skulking, waiting on the land – deep in the bushes and trees (still largely hidden in this evergreen utopia), and occasionally, rarely, when the sun shone strongest (stretching the temperature from below freezing to over 20 degrees centigrade in a matter of hours), the Song Thrush sang. The silence pierced by one of the most famous songs of the wild.

My winter patch had other surprises for me. Occasionally the silence was broken by a passing Tit flock.

Long-tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus)

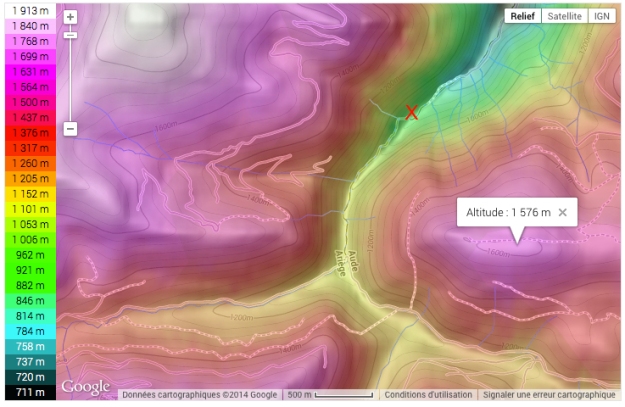

Long-tailed Tit, Great Tit, Blue Tit. The flocks foraged in the Aleppo Pines on our hillsides joined by their mountain-loving cousins, Crested Tit. Larger numbers than I have ever seen before on the patch. The sparkling white peaks in the distance were a clue that that these stunning birds had moved down in altitude to find food in pines not frozen solid and not covered in a thick coat of snow.

European Crested Tit (Lophophanes cristatus)

We are still several months away from our Summer migrants joining us again (the Nightingale, the Melodious Warbler, the Whitethroat, the Chiffchaff, the Sub-Alpine Warbler are all hundreds and thousands of miles South on a different continent), but there are some warblers that stick it out. In fact I was blown away how many bushes would tick and rattle at me with Sardinian Warbler and Blackcap, both here in large numbers.

The bushes and trees of the maquis hold other winter secrets too. Firecrest are everywhere – moving through the Box, Holm Oak, and even navigating the tightly twisted branches and densely-spined leaves of the Kermes Oak. I remain convinced that this little king is the most numerous bird on the patch. Short-toed Treecreeper shuffle up and down the narrow twisted trunks of maquis growth, Wren peek out and occasionally call territorially, as does the Robin, ticking like an old pocket watch and signalling places where the ground has been disturbed.

Roe Deer tracks mosaic the mud, but sometimes the disturbance is more complete. I pushed my way through bars and thorns to be inside a Holm Oak wood and could smell and tell the recent presence of Wild Boar.

Holm Oak (Quercus ilex) and boar-disturbed ground

The winter green (as so much of the maquis is evergreen) was occasionally punctuated by the seemingly unseasonal blossom of Strawberry Tree bell flowers whilst other trees of the same species were still full of fruit.

Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo)

Its name proving to be a misnomer as my wife and Sister-in-Law happily ate several of the crimson balls: ‘Arbutus unedo‘ or ‘eat once’ as their appealing fruit are supposedly bitter.

Fruit of the Strawberry Tree

The clear blue skies of the patch are rarely crossed by plane or passing bird – I have never seen a gull, duck, or goose fly over the patch, for example. Occasionally a comet of feather would arch over in a parabola from low to high to disappear, again low, in the undergrowth displaying the stumpy tail of the Woodlark – whose song I long to hear again in the warmer months, but who is now, silent.

Sometimes, too, the great silent blue was brought to life by the tinkling of Goldfinch (I counted a flock of thirty-plus one day) or the odd chup-chup of the Chaffinch. Last winter I added Hawfinch to my patch list. This year the silence was broken more comprehensively by a single male Siskin moving through the tops of the pines – it is the first and only Siskin I have seen on this patch in nine years of regular visits.

Goldfinch and Chaffinch were only beaten in their airborne vocal reliability by the cronking of our resident Ravens.

Common Raven (Corvus corax)

During this visit, the most complete shattering of the silence – apart, perhaps, from the distant boom of hunters’ guns – was in the gathering of the largest flock of Raven I have ever seen (in fact it was two flocks totalling some 40 birds).

An unkindness of Raven

The collective noun from, medieval venery, for Ravens is an ‘unkindness’. I consider this to be unkind in itself. I watched them swirl and court and ‘play’ in such a sociable manner high up on the thermals that I: a) could not believe their attention was really on any ground carrion; or b) simply disagree with the noun imposed on them.

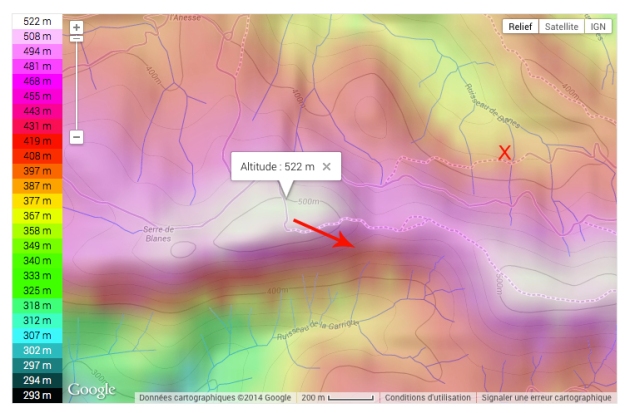

To truly work a patch, it helps to have a clear idea of the shape, size and boundaries of it. With my London patch, I know this well as it is set out in maps and was agreed by others before I moved to the area. In France it is not so clear, partly because I am the only birder working the patch. The ownership of the land is not physically marked and is archaically legally patchwork (no pun intended) in nature. The boundaries are flexed by the distance I walk and were pushed to their limits this trip when I found two new birds for my patch list. I now decree it to be the land surrounding the house stretching in all directions up to the immediate vicinity of surrounding roads and villages (I must admit that this makes it really rather huge in size).

On one walk to a nearby village when the houses were in sight, albeit over 100 metres vertically below our hillside track in elevation, I heard and saw the first Carrion Crows I have recorded on the patch.

On another walk from our land to another village I finally saw a bird that has been the top of my patch wishlist for several years: the Griffon Vulture.

Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus)

The enormous bird circled around a hilltop several times before flying high right over our heads and fast off South back towards the Pyrenees. It did all of this without beating its giant wings once and, of course, it did it all in absolute silence.

I was mesmerised but very happy. The tenth raptor tick for this patch for me (dare I hold out hope for Lammergeier and Bonelli’s Eagle? Of course I do – I am an optimistic birder! Black Vulture may be pushing it a bit, but I live in hope) and I still haven’t seen Black kite and Booted Eagle on the patch which are both common in the area and I have seen many times further afield.

In the last two days, the weather has changed and the silence has been shattered by strong winds. Tough birding has also just got even tougher, although my wife and I stood on top of a hill yesterday and looked across the valley at a pair of Red-billed Chough battle expertly (but somewhat less acrobatically than in calmer weather) against the wind whilst hugging the rock escarpments known within the family as ‘Eagle Peak’.

30. That is the number of different species of birds I have counted in the few days we have been out here. That is around half what I would expect to tick off on my patch in London at the same time, but the experiences that come with these birds often make me stand still in awe and silence.