A sense of ‘place’ is very important to me. Understanding my ‘Patch’ in the UK requires understanding a bit about East London, Epping Forest, Essex, English parkland, scrub, grassland, and woodland.

I have written many words about the ‘place’ of the French ‘Patch’; the Mediterranean scrub (maquis and garrigue), the foothills of the Pyrenees, Aleppo Pine woodland etc. Context is important, whether that be geographical, geological, climate, botanical, etc.

For these reasons, I am slightly obsessed with mapping the land. I have done a bit of that before, but I wanted to share some free online tools that I find super useful when trying to understand the patch that I study.

First, location. The blue dot below shows you how close we are to the Mediterranean and to the Pyrenees.

Thanks to Google Maps for this and the other maps

Second: area. The ‘Patch’, as I define it, sits within a trapezoid of four small French villages. The total area that I watch for birds and other flora and fauna is just under a whopping 10km squared. I know this because a website allows me to calculate it pretty accurately:

Remember that I am the only person who ‘works’ this Patch from a wildlife perspective, and only a few times a year. To set it in broader context, it is interestingly almost exactly twice the size as my London Patch (France c.10km2 vs Wanstead c.5km2) which is Wanstead Flats, Wanstead Park and some intervening streets combined as well as being ‘worked’ or watched by several other people on a regular basis.

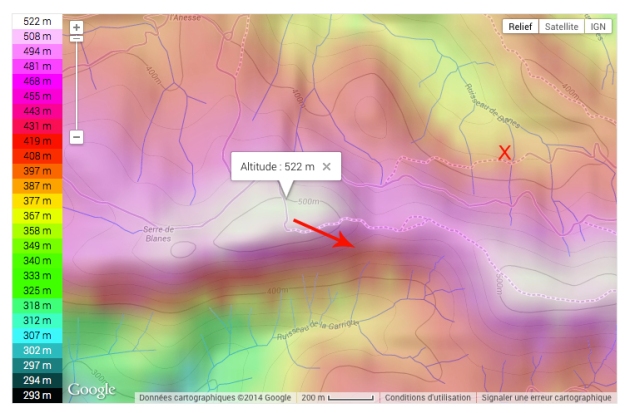

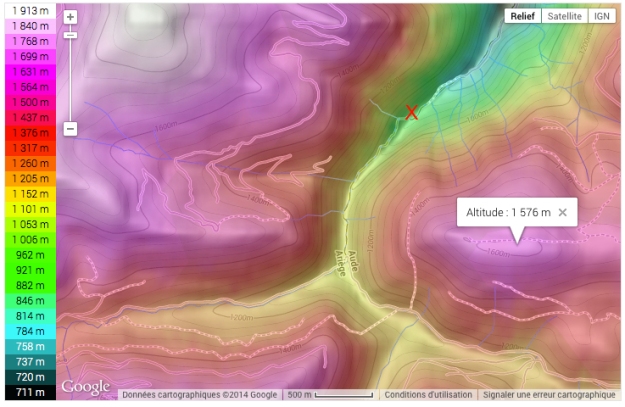

In terms of elevation, the lowest point on the French Patch is around 166 metres above sea level whilst the highest point (Mont Major) is a pretty lofty 534m. My wife took the picture below of me standing on the highest point looking down over the Southern valley with the Pyrenees away in the distance.

For another reference point, the Wanstead patch is exceedingly flat and low in comparison; ranging from 7m above sea level to 30m (that is the height of a medium sized tree!).

Although I know my way around the Patch pretty well now after a decade of regular walks, I have still found it useful to map key landmarks and paths on top of Google Map images to help me get a sense of scale.

The entire Patch and surrounding villages

To give a sense of perspective, the red marked ‘track’ (or ‘chemin’), that we have to drive to reach the house, is almost exactly 2km long. If you are wondering how I can be so precise, it is because Google Maps has a helpful tool to measure distance accurately.

Zooming in a bit from the colour-coded annotated map above, I have produced several more detailed maps showing routes of walks and landmarks, such as the example below. As you can see, I don’t exactly use scientific or formal names for the routes and places on the Patch (hence the ‘steep bit’) and will sometimes name places after wild features or species that I associate the area with, e.g., “Bee-eater Valley”, “Holm Oak Wood”, and “Griffon Vulture Hill”.

Using the nifty 3D functions on Google Maps (no, this isn’t a sponsored post), the topography is brought to life a little more by the the image below, with the house marked with a blue dot and the highest peak to the top left at the end of the orange line.

The main stream which rises on the Patch and flows West then North towards the little town of St Pierre-de-Champs is named after the land (or vice versa). ‘Ruisseau de Blanes’ is some 5km long (again thanks to the tool on a well known free online map) and joins a tributary of L’Orbieu river which, in turn, joins the river Aude (which shares a name with the department/province we live in) and flows into the Mediterranean just North of Narbonne.

For much of the year, the stream bed of Ruisseau de Blanes is dry above ground. As part of my obsession with understanding every bit of the Patch, the other day I decided to walk along the bed and track my way to the edge of the Patch. This is far easier said than done, as some sections of the river are inaccessible, extremely steep, or heavily overgrown.

Looking back upstream with the outcrop we call ‘Eagle Peak to the top left

Scrambling my way over an ancient rock fall on the stream bed

At points the silence, that is so alien to my London sensibilities, was almost overwhelming. No traffic, no planes, no running water, no summer insects, very little bird noise. A Raven‘s deep croak echoed in the valley and got louder and louder until the giant corvid came into view low over the trees. I was staggered how loudly I could hear its wingbeats; wingbeats which sped up rapidly when the bird caught sight of me. The different pitches of the wingbeat of every bird that I came across became clear in the silence, even the high speed flutter of firecrest and Goldcrest as they darted from tree to tree.

It was a jolly adventure. Jolly that was, until I worked my way back the way I came and realised I had lost the point at which the woodland path joined the riverbed. I then remembered that when I had broken out of the heavy maquis onto the stream bed, I had taken a photograph looking downstream. I studied the picture and walked backwards trying to make the puzzle fit. Eventually, I found the right point (took another picture – see below – to illustrate the story) and then found the hidden path to the right.

Image to the left taken about an hour before the one on the right

Of course, we have lost so many of the ancient instinctive skills of tracking and mind mapping the land that our ancestors would have used daily (and without the use of camera phones and Google Maps!)

Throughout history I imagine we have always looked for features to give us a sense of place. On the Patch we have a tiny remote chapel that is but a node on a huge long pilgrimage walk.

I often drop by, noting the goat droppings on the floor and the rusty little cross on a makeshift rock altar. But yesterday I noted a new feature, above the crucifix and some christian graffiti was a twisted stick. I don’t know what this stick was, but I perceived it as an echo of a more ancient religious mandala; a pagan offering, perhaps, helping to place this little religious building in the natural world around it. A sense of ‘place’ that seems to stand outside of time.